From Subculture to Mainstream: How Alternative Movements Lose Their Edge

- Pages: 5

- Word count: 1005

- Category: Culture

A limited time offer! Get a custom sample essay written according to your requirements urgent 3h delivery guaranteed

Order NowSubcultures are traditionally understood as forms of resistance—whether aesthetic, social, or political. They emerge on the margins of society, develop their own norms, language, styles, and values, and define themselves in opposition to dominant culture. Yet almost every influential subculture eventually follows the same trajectory: from marginality and protest to recognition, commercialization, and integration into the mainstream. This shift is often described as a betrayal of original ideals, but in reality it reflects deeper dynamics between culture, markets, and power.

Why Subcultures Emerge: Protest and the Search for Identity

The emergence of subcultures is almost always linked to a sense of mismatch between individual experience and dominant social norms. Youth movements of the late twentieth century—punk, hip-hop, grunge—arose in contexts of economic inequality, social frustration, and limited avenues for self-expression. Subculture became a way of declaring, “We reject the rules we’ve been given.”

The emergence of subcultures is almost always linked to a sense of mismatch between individual experience and dominant social norms. Youth movements of the late twentieth century—punk, hip-hop, grunge—arose in contexts of economic inequality, social frustration, and limited avenues for self-expression. Subculture became a way of declaring, “We reject the rules we’ve been given.”

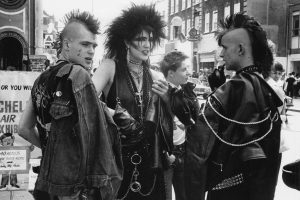

Crucially, protest within subcultures is rarely purely political. More often, it is existential and symbolic. It is expressed through clothing, music, body language, and behavior. Torn jeans in punk culture, the aggressive visual language of graffiti, or the deliberate sloppiness of grunge were not just stylistic choices; they were visible refusals of middle-class ideals of respectability, order, and success.

Subcultures also play a key role in identity formation. They create a sense of belonging in a world where many individuals feel alienated or invisible. Shared codes—music, slang, rituals—allow participants to recognize one another and build alternative communities. At this stage, subcultures are usually closed and wary of outside attention, because distance from the mainstream is what gives them meaning and coherence.

How Mass Culture Absorbs Alternative Movements

The transition from subculture to mainstream rarely happens overnight. It usually begins with growing interest from media, the fashion industry, or the music business. Alternative styles are visually striking, emotionally charged, and easily recognizable—qualities that make them commercially attractive.

The mechanism is relatively straightforward. Mass culture does not destroy subcultures directly; instead, it extracts their most recognizable and marketable elements while stripping them of context. Punk becomes a design aesthetic for jackets and accessories, hip-hop turns into a global music genre and fashion industry, streetwear moves from sidewalks to luxury runways. The radical ideas that once gave these styles meaning are softened, diluted, or removed entirely.

This process is often described as co-optation. Protest stops being threatening once it can be sold. In fact, commercialization often creates an illusion of acceptance: what was once marginalized is now celebrated in advertising and popular media. For some participants, this feels like a victory—their culture is no longer mocked or excluded. For others, it signals a loss of authenticity.

Commercialization is almost inevitable because subcultures do not exist outside society. They rely on the same media channels and economic structures as the mainstream. Once a movement becomes visible, it becomes legible to the market—and visibility invites appropriation.

Loss of Protest or Transformation of Resistance?

A common assumption is that once a subculture enters the mainstream, it “dies.” This view, however, oversimplifies what actually happens. More accurately, protest shifts or fragments. One part of the subculture becomes a mass-consumed style, while another retreats into the underground, radicalizes, or redefines its goals.

Punk as a mass image has largely lost its shock value, but that does not mean the punk ethos has disappeared. It survives in new forms—DIY culture, independent labels, local scenes. Similarly, hip-hop, despite becoming a global industry, continues to produce localized movements that retain strong elements of social critique and political awareness.

Interestingly, commercialization can sometimes sharpen critical awareness. When symbols of resistance become commodities, participants are forced to reflect on what exactly they are resisting if their style is sold in shopping malls. This identity crisis can generate new forms of opposition, often less visible but more conceptually deliberate.

In this sense, the loss of “edge” is not always an ending. It can signal that an earlier form of protest has exhausted its potential and needs reinvention. The history of subcultures is cyclical: as one wave is absorbed by the mainstream, another begins to form on the periphery.

What Remains After Mainstreaming: Legacy and Cultural Impact

Even when fully integrated into mass culture, subcultures leave lasting traces. They reshape language, aesthetics, and social norms. What once seemed radical gradually becomes acceptable. Streetwear has transformed ideas of what counts as high fashion. Alternative music has expanded the sonic and thematic boundaries of popular culture. These changes are difficult to reverse.

Subcultures also influence how future generations express themselves. They create an archive of images, practices, and ideas that can be revisited, reinterpreted, and repurposed. Even in commercialized forms, they retain echoes of their original meaning, however muted.

Finally, protest does not need to be permanent to be meaningful. A subculture can fulfill its historical role—naming a problem, pushing boundaries, giving voice to dissent—and then dissolve into the mainstream. From this perspective, its apparent defeat may also be understood as a form of success.

Conclusion

The journey from subculture to mainstream is not simply a story of loss, but a complex process of cultural evolution. Commercialization is inevitable because society tends to absorb whatever becomes influential. Yet even after losing their initial radicalism, alternative movements continue to shape culture, language, and ways of thinking. Protest does not disappear—it changes form, making room for new and still-unrecognized expressions of resistance.